A BRIEF HISTORY OF ALL SAINTS

You will notice that this Guide is a very personal one: it is more about people than things. This has been done deliberately because the Church itself properly understood is people. It is the people of God in any one place. The building is simply the shell inside which the Church meets. I hope it has given you a fuller understanding of the richness of our Christian heritage in Runcorn, and I hope that it will encourage you to find your place within the fellowship of Christ today.

D.G. Thomas - Vicar Easter 1978

Introduction

Our Church has a long and interesting history and there is much of interest to see in it. The problem-that has faced me in compiling this Guide has been to decide what to include and what to leave out. In the end I decided to write about the things that interest me, in the hope that they will interest others also.

THE CHURCHYARD

The first things we notice on approaching the Church are the cast-iron railings and the heavy gates in Church Street. The lock has the inscription, 'J. Donald, W. Bankes, Churchwardens 1833'. It was in this year that the ancient churchyard was extended southwards and the new railings fixed. Experts consider them very fine examples of early nineteenth century ironwork.

In the far right hand corner is a sub-station. This sandstone building was originally the 'Hearse-house', and presumably built at the same time as the railings, as we know that an earlier Hearse-house was built on to the old Church. In these early days there were no Funeral Directors in the country. The local joiner would make the coffin and it would be taken to the Church in the communally owned hearse drawn by horses from the farm.

The Churchyard itself is now a lawn garden. The old tomb stones were laid flat to form paths in 1963, after each stone had been photographed and recorded. The oldest stone is beside the soot-encrusted sun dial. The date 1626 is still legible but nothing else can be seen on it.

THE OUTSIDE OF THE CHURCH

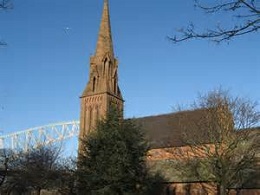

The whole Church was as black as the sun dial until the fabric was cleaned in 1973. We can now admire the pink sandstone from the Runcorn quarries with which it was built. One of the best views of it is perhaps the road bridge, crossing from Widnes, as we look down on it set in the green garden.

The Church was designed by Anthony Salvin in the style of the mid-13th century (Early English) and was consecrated in January 1849. The height of the spire is 161 feet. It replaced older Churches which stood on the same site and of which we shall have more to say later.

Nowadays we use the door in the Porch on the south side, reserving the West door for very special occasions, but many years ago the North door was used. There was a path from it leading through trees along the bank of the Mersey, but that was in the days before either the Manchester Ship Canal or Mersey Road were built.

The little door to the left of the Porch leads by a spiral staircase down to the boiler house and up to the Ringing-chamber and Belfry, in which are eight bells.

The Church doors are all of traditional style. They are made of two thicknesses of oak planking, one vertical and the other horizontal, bound together by heavy iron bolts. This is a reminder to use that life was often very violent and dangerous for our forbears. If the villagers were inside and the door securely shut with heavy beams they had some protection from the Vikings' axes or the robber bands' assaults.

INSIDE THE CHURCH

On entering the Church we find a light oak literature table on our left. This is of interest in that it was given to us by the Trustees of Greenway Road Methodist Church just before their church was demolished.

THE BEGINNINGS

If we turn to the right we see two windows, picturing Queen Ethelfleda and her father King Alfred. The Queen holds a model of a church, indicating that she is commemorated as the Foundress of our Church. The story goes back to the year 915. At that time England was divided into several small kingdoms. Ethelfleda was Queen of Mercia, middle England, bordered by the Mersey on the north. In this year she came to what is now Runcorn to build a fort on the bank of the river at its narrowest point, where the railway bridge now stands, and as might be expected from the daughter of her father, she built a Church nearby.

The earliest dedication given to the Church was St. Bertelin. Who was he? Nobody seems to know, but it is interesting to notice that the Church at Barthomley, in south Cheshire, has the same name, and that the village go its name from the saint. It is possible that he was an early hermit or other holy man remembered with honour at the time of Ethelfleda.

If we move on along the aisle we see near the lectern an early 12th century grave slab. This is the oldest object in the Church. The first reference to the church in recorded history was a generation or two before this slab, when Nigel, first Baron of Halton, presented 'the Church of Runcorn on Wolfrith a priest'. This was soon after the Norman Conquest of 1066. The Normans were .great builders of castles and churches. It is more than likely that at this period a new stone church was built to replace the earlier Saxon one. At this time the Church was dedicated to St. Mary and St. Bertelin. At a later date the name St. Bartholomew was added, and finally, the name All Saints' was given in place of the others.

THE CONTENTS OF THE CHURCH

THE MEMORIAL CHAPEL

This Chapel, at the East end of the South aisle, was dedicated after the First World War. The names of those from the Parish who died in the two wars are inscribed on the walls.

THE LECTERN is of carved wood shaped as an eagle. This is a very convenient shape for holding a bible, but there is more significance in the shape than that. In early days the four Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, were given as their 'signs' the four living creatures described in the Book of Revelations as being by the throne of God. One of these creatures was 'like an eagle' and this was used as the sign of John. In the Middle Ages the Mass ended with the Last Gospel, St. John, chapter 1. This was often read from a lectern shaped as an eagle. After the Reformation there was great emphasis put on reading the scriptures and so lecterns were in great demand. A new and wider use came to be found for these old eagle stands, and since then new lecterns have often been made in the old traditional style.

The Bible is read in every act of Christian Worship. In recent years there have been many translations into modern speech. Many find them helpful but some regret the passing of the beauty of the Authorised Version of 1611.

THE PULPIT is on our left before we move into the Chancel. It is well worth having a careful look at the beautifully carved panels depicting Christ in various forms: The Light of the World, The Good Shepherd, The Sower.

THE CHANCEL STEPS will appear of little interest to the average visitor, but they have been the site of great events in the lives of many. It is here that the Bishop has laid his hands in Confirmation on the heads of so many boys and girls and older people, and it is here again that countless men and women have made their marriage vows and joined their hands together in matrimony: 'What God has joined together let no man put asunder'.

THE CHANCEL. This is one of the best features of the Church, with its width, its fine proportions and large windows. The clergy and choir stalls are on either side. The decorated timber work on the choir stalls came from the old Church. The organ is behind the screen on the north side, but the detached manual behind the stalls on the other side. The memorial tablets on the walls are all of the Brooke family who lived in Norton Priory. They are buried in a vault under the chancel.

THE ALTAR is the most sacred part of any Church because it symbolises what the Christian religion is all about. It is here that people have come every Sunday for over 1000 years to kneel and offer themselves to God. In return they receive the sacramental bread and wine, the means by which Christ comes to them afresh and goes with them out into the world.

Some of the Communion vessels have a long history. We have a chalice believed to date from Elizabethan times, but with later repair work. There is a very fine silver chalice and pattern dated 1670 and a silver flagon with the date of 1704.

The altar frontal used at Festivals, and the Mother's Union banner, sometimes in the sanctuary, are fine examples of modern needlework specially made for the Church.

THE VESTRY is entered from the chancel through the door on the North side. It is here that the marriage registers are signed and indeed in the safes are kept all the registers of Marriages, Baptisms and Burials since 1558. Here are kept also the ancient Churchwardens account books. These cover what was done in early days in the way of local government; being concerned with such matters as road repairs, impounding stray dogs and poor law administration.

THE NORTH AISLE

If we move back to the other side of the pulpit we come to THE FONT. The original Baptistry was in the extreme South West corner of the Church, in what is now the Choir vestry. The font originally had a high wooden cover, but that has disappeared. The font was later moved to a position just inside the main door, but as this was not satisfactory it was moved to its present position some 15 years ago.

The Font is large not just because it is situated in a large Church, but so that, if desired, a child could be baptised by immersion. In the days of the Gospels it was usual to baptise by immersion in a river. The significance was that as a person went under the water they died to sin and in a sense were 'buried with Christ'. The rising again from the water is symbolic of 'rising with Christ' in the new life of the Spirit. The symbolism of baptism remains the same even though in the chilly climate of northern Europe it has been usual to pour water over the person being baptised at a font.

THE OLD ALTAR TABLE

The table behind the font is most interesting. An inscription tells us that it was the gift of Sir Richard Brooke, Baronet. It dates from the late 17th century and was the Holy Table in the old Church. It is a single pedestal table, supported by four pelican heads and as such is almost unique. The ancients believed that the pelican plucked feathers from its breast to nurture its young, even though to do so meant shedding its own blood. This was a popular analogy in the 17th century of the work of Christ who shed his blood on the Cross for our salvation.

THE OAK SCREEN. NORTON PRIORY AND CHRIST CHURCH

The screen between the font and the organ deserves careful examination. It is the work of the late Tyson Smith, of Liverpool, one of the greatest carvers in wood or stone of this century. The two coloured shields are the first things that take our attention. The one on the left is of the Diocese of Chester, but the other is more of a puzzle. It portrays a cardinal's hat. In real life this would have seven tassels but in art two suffice. The hat in fact is Wolsey's and is the badge of Christ Church, Oxford, who for 400 hundred years have been the patrons of the parish with the right to appoint the successive vicars. If the riddle were asked, 'What is the link between an Oxford College, a King's Chancellor (Wolsey) and Runcorn', the answer would be Norton Priory. The Priory was founded in Runcorn in 1115 and the Church was given to it. The Church served the monks for their place of worship and they appointed the vicar. Twenty years later they moved to a new site at Norton and over the years built the great Abbey Church and complex of buildings that have been revealed recently by archaeological digs, but they still appointed the vicars to Runcorn. Some of these priests have their names carved on the screen with the dates of their appointment. Four hundred years later King Henry VIII began to suppress the monasteries and Norton was closed and its property seized by the Crown in 1536. Thomas Wolsey, Chancellor a few years earlier, had founded a new College in Oxford, originally called Cardinal's College. After Wolsey's fall from favour Henry took over as Patron. He enlarged it and changed its name to Christ Church. He did this with the use of money and property he had seized from monasteries, including Norton. This is how the Church, the ancient tithes, and land that had belonged to Norton came to be given to Christ Church.

TWO INTERESTING VICARS

Two names in the list of vicars arouse curiosity. Why does Thomas Fletcher's name appear twice, in 1525 and 1539? It would have been the Abbot of Norton who nominated him for the appointment in the first place, and then, in 1536, the Abbey was suppressed. Thomas Fletcher must have felt very insecure in his living when he saw the Abbot and monks turned out of their old home with small pensions. It seems that he managed to get the Bishop to confirm his appointment in 1539. He continued as Vicar of Runcorn until 1571, and what tremendous changes he passed through. He began as a 'catholic priest' using the Latin mass and accepting the authority of the Pope. In 1539 he would have had to renounce the Pope and accept the King in his place. Ten years later he would have changed to the new English Prayer Book, and then, during Mary's brief reign, have resumed the old Catholic practises. Finally, when Elizabeth came to the throne he would have appeared again as a good reformed English Churchman. In fact he almost beats the Vicar of Bray!

It would be easy to think of such a man as a mere time-server, but he probably represented the great bulk of Englishmen who felt that all these outward changes were the concern of the great folk only and that the life of the Church of God in the parish went on irrespective of them.

The Revd. Thomas Breck, ejected in 1662, must have been a very different sort of man. He was one of the Presbyterian ministers made incumbents in the Church of England during the Commonwealth. After the Restoration, when King and Bishops were restored to their positions, such ministers were presented with the choice of either accepting episcopal ordination or of resigning their offices in the Church. Thomas Breck was one of those who refused to compromise his firm puritan principles. We can honour him for the sacrifice he made.

THE ANCIENT PARISH

Notice what the carved screen says about the size of the Parish. It included the chapelries of Halton, Aston, Daresbury and Thelwall. It extended some seven miles by four. This area has since been divided into 10 parishes.

THE MEMORIAL TABLETS

These were originally in the old Church. Those on the north wall include some which commemorate distinguished 17th, 18th and 19th century vicars.

The Revd. William Finmore was Vicar from 1662 until his death in 1686. For much of this time he was also Archdeacon of Chester and in fact he died and was buried in Chester.

The fascinating, but rather gruesome, tablet has many interesting features but two points in particular intrigue me about it. It commemorates his first wife Phillipa, whom we are told was buried in the Church together with another 'devout woman and good wife', Ann Breck. This in itself is most unusual but the fascination increases as we notice that Ann Breck shares the name of the previous Vicar, ejected in 1662. Could she have been Thomas's wife? Could the two wives have become close friends even though their husbands were so opposed in politics?

I don't suppose we shall ever be able to answer these questions but here is surely a wonderful plot for a historical novel.

The other particular point of interest about this memorial is the date, January 30th 1671/2. It was not until the mid-18th century that the year started in January. It formerly began on March 25th. January 30th would therefore be 1671 in the old reckoning but 1672 in the new.

THE ALCOCK MEMORIAL

This commemorates the Revd. Thomas Alcock, Vicar for 42 years, and his more famous brother Nathan, a celebrated physician. Both were born and brought up in the parish at Aston. Thomas was also vicar of St. Budeaux, by Plymouth, a place he greatly loved, and so it does not seem likely that he did much in Runcorn, although it is possible that he built the stone wall around the Vicarage grounds. He appointed a succession of curates to serve the parish.

The REVEREND WILLIAM KEYT, 1799-1816, was the first of the modern style of vicars. His memorial speaks of an uninterrupted residence of 16 years — a remarkable thing in those days. He is described as the poor man's friend. I think that he deserves this tribute not least because it was through his efforts that the Sunday School, and later. Day School were built in 1811.

The REVEREND JOHN BARCLAY, Vicar from 1845-85, during whose ministry the new Church was built, has his Memorial behind the lectern.

Two other Memorials are behind the organ and cannot at present be seen.

Other Memorials on the walls preserve the memory of a number of leading citizens of the early 19th century, as do also many stones in the Churchyard. They help to remind us that we are only here for a few years and that others will be following after us. We should thank God for all who have loved and served him and pray that we too may live useful lives so that we can pass on to those who come after us a goodly heritage.

THE CHURCH MOUSE

I am assured by many parishioners that if you look at the carved tracery of the stone pillar nearest to the Keyt Memorial you will see a mouse peeping at you, but I must confess I have never been lucky enough to see it, perhaps I make too much noise.

AT THE WEST END

There are three things of particular interest. On the West wall itself now hangs the Royal Coat of Arms, originally in the old Church. This reminds us of the close connection that has existed in England between the Church and the Royal family.

The ancient Table of Benefactors is now very faded, but it lists gifts given to the Church, for the poor and for roads, given in the late 17th and 18th centuries.

Nowadays we do not need to give to the Church for road repairs, and not so greatly as formerly for poor relief, but the need to give for the maintenance of the Church and its work is greater than ever.

If we stand by the door to the Choir Vestry, and look upwards we see a carved stone head on both sides. That to our right is believed to be a representation of Canon John Barclay, Vicar at the time of rebuilding. I like to think that the lady to our left is Mrs. Barclay, but that is guesswork. I am interested to notice that Canon Barclay is wearing a Canterbury Cap, the traditional head-gear of the Anglican clergy, and a type of hat that for warmth and wind resistance cannot be beaten. It is also clear from this figure, and from his Memorial, that he was no supporter of the 'short back and sides brigade'.